Populism: the New Language of Politics

By Claudia Devda | 23rd of November, 2025 | 4 min

How often do we find ourselves labeling a politician as “populist”? Yet it is difficult to think of another term so loaded with ambiguity, used both to describe right-wing and left-wing leaders, to denounce authoritarian tendencies and to celebrate the return of the “true people” to the political stage. As Michael Cox writes in his essay “Understanding the Global Rise of Populism”, it would be wrong to think of populism as merely a media trend or a passing phenomenon: it represents instead a profound transformation in the very way politics is conceived and practiced.

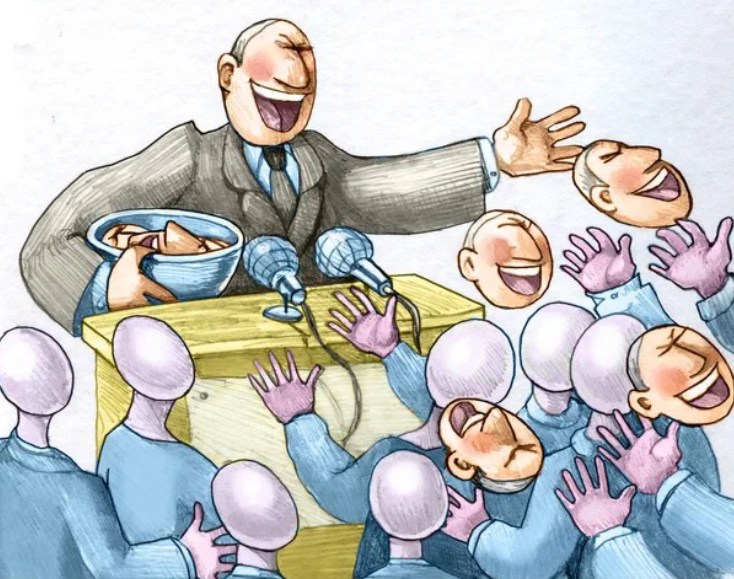

If we look back at the politics of the post-war period, the contrast with today is sharp. Parties used to represent solid ideologies and long-term visions, politics was the art of mediation and compromise indicated democratic maturity. Today, however, the logic of immediacy and impulsiveness prevails: tweets, rallies, slogans, and promises dominate the political space. Whereas in the past populism was sporadic (think of rural America in the late nineteenth century or Latin American movements after WWII), it has now become a global trend. The idea that “the people,” feeling no longer represented, must reclaim power from an elite perceived as distant or even corrupt has become one of the most powerful symbolic and rhetorical levers of the twenty-first century.

When we look to the West, we tend to imagine populism as a primarily American phenomenon: after all, the U.S. political landscape is polarized between two parties and two opposing ways of seeing and shaping policy, often pushed to extremes. Yet in Europe the populist map has become surprisingly diverse too. On the right, parties such as Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National, Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland, and Italy’s Lega build their appeal on defending national borders, opposing immigration and criticizing European elites. A 2024 study conducted by the European Center for Populism Studies shows that right-wing populist forces obtained on average 19% of the vote across the EU, compared to 10% five years earlier. But there also exists a populism of the left, embodied by movements like Podemos in Spain, Syriza in Greece, and certain segments of the Italian Movimento 5 Stelle: a populism that speaks of redistribution, social justice, and “the people vs the markets,” opposing not migrants, but financial power and global economic elites. Though distant in values, these two perspectives share the same narrative structure: the belief that society is divided into two opposing groups, the virtuous people and the ruling elite, and that only a charismatic leader can “heal” that fracture, simplifying the world into black and white.

Therefore, a once structured, formal and somewhat bureaucratic approach to politics, mostly consisting of interviews and newspapers, is being replaced by disintermediation: a communication through social networks that is immediate, personalized, and emotional. Political language has become more visual and performative. The result is certainly a more immediate kind of politics, but also one that is more fragile and risky, where the complexity of problems is too often surrendered for the sake of simplification.

Personally, I believe that this does not mean populism is inherently negative. In many cases it has reopened spaces for participation and given voice to forgotten social groups. However, when populist rhetoric turns into contempt for institutions, delegitimization of dissent, or the cult of the leader, it can erode the very foundations of liberal democracy. Born from the ideals of dialogue, pluralism, and critical thought, the European Union and its member governments should now more than ever reflect on this growing demand for radical alternatives, that, while dividing communities, reflect not only citizens’ economic insecurity but also an increasing distrust in expertise and competence. Perhaps, rather than demonizing populism, we as citizens should reflect on the reasons for its effectiveness and develop greater awareness of the value of dialogue and confrontation, so that uncritical choices and impulsive reactions do not undermine the potential and progress of our democratic communities.

Claudia Devda is a third year bachelor student at Bocconi University studying Economics and Management.